Humankind – -apkrig

Contents

Multiculture on the other

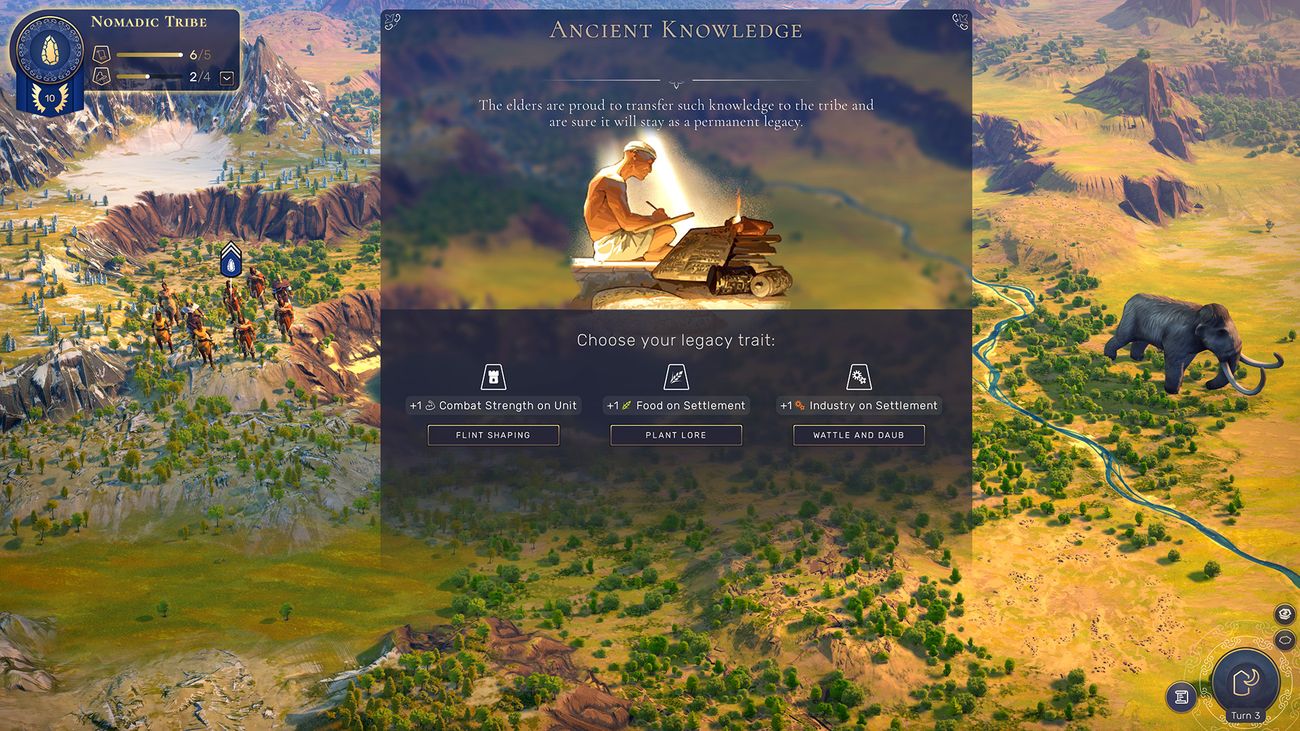

This element is the mixing of individual civilizations. In the introductory phase, for example, you play for the ancient Assyrians, hunt mammoths, build the first primitive cities surrounded by inefficient farms. You invent the bike, fishing and so on. And then, when you are advanced enough, you will move on to the next age, to classical antiquity.

In Civilization, this would not mean anything to you other than access to new buildings and units, but Humankind will allow you to press the big red RESET button. You can choose a completely new civilization, in ancient times such as the Celts or Huns. Click – and all your bonuses and civilizational qualities will change immediately, plus you will retain some belonging to the previous nation.

Of course, it doesn’t make much sense in terms of storytelling. The authors argue that every civilization is on the shoulders of its ancestors and that mixing cultures is perfectly common, which one might agree with, but historians and sociologists would probably have rolled their eyes if Phoenician seafarers had been in a few centuries. transformed into the Mauritian Indians.

But let’s leave out the story implications for a moment and discuss what it means for gameplay. And it doesn’t really mean anything to her. For example, in the ancient era, I chose the Egyptians, an architectural civilization that gains more fame the more buildings and districts they build. And fame is important – only thanks to its sufficient accumulation will you win the game, forget about different types of victories as in Civilization.

When I arrived in a new era, I had a choice of many new nations – warriors, scientists, farmers. But I chose Maya, another builder, because I had the whole economy completely optimized for their style of playing.

I asked the authors of the game about this in our interview. Why should I choose a nation with a different style of play at any time? Is there a benefit? “Good question,” the developers replied, peering at each other a little uncertainly. They gave some examples where change could pay off – of course, if war broke out and I needed military skills for defensive reasons, I would become a Roman, for example. But I’m not entirely sure why I would change from an agrarian to an esthete, for example.

It does a bit of trouble in diplomacy, because it is confusing when you connect with your southern neighbors Chetita at the beginning of the game, after a while you look beyond the borders and find out that you are already in alliance with the Goths, soon replaced by Franks and color the whole faction thus lacks a slight continuity.

I understand that Amplitude loves asymmetry, that it wants the community to come to the craziest builds possible to find out that when you move from Koreans to Germans, such and such synergies will win the game. So far, I’m not sure that it added anything to my specific gaming experience.

Beautiful and pleasant

I just criticized the biggest source of developer pride, so I should be logically dissatisfied with the whole Humankind. But I’m by no means because, as I wrote at the beginning, the rest is great – and surprisingly different from Civilization.

Perhaps the most fundamental difference in feeling is that Humankind is played incredibly comfortably. The user interface is absolutely intuitive and I didn’t really need a tutorial for more complex concepts. The moves spill away at a crazy pace, you don’t have to wait for many opponents’ moves, because they all happen practically simultaneously – and you can plan further steps during them. There really isn’t time to get up here and go make coffee between moves.

This is helped by the fact that Humankind is far from intensive to mic. Compared to Civilization, you own significantly fewer cities, but they control a much larger area of the map. You group units into armies. Instead of a huge number of building fronts and military dolls, you only care about a few key pieces, around which the fate of your entire empire revolves. When I shared this experience with the developers, they shone like sunshine and confirmed that yes, they were really trying to achieve exactly the effect I had just described to them (and you).

The game is also very, very handsome. If you didn’t like the colorful, stylized graphics of Civilization VI, Humankind might be aesthetically pleasing for you – and I, who liked the Sixth Civic, sometimes stared at the screen, which is basically a map and a collection of glorified Excel spreadsheets. , excellent sign. I’m just a little sorry that the construction of wonders of the world is not accompanied by architectural animation as in the competition…

Lots of good ideas

On the contrary, what I am certainly not sorry about is the many elegant solutions concerning both internal and external policy. During the game, for example, you shape your own state ideology not by choosing fascism or liberal democracy from the tree of technology, but simply by solving dilemmas.

For example, you come up with a printing press. You have to decide whether to allow access to it for everyone, which will make the development of new technologies more efficient, or you will regulate it to be more influential. But in addition to short-term effects, this choice will move you on the axis between freedom and dictatorship or between individualism and collectivism. State institutions, along with all bonuses and maluses, are formed organically.

Wars that arise from realistic diplomatic crises are also very natural. Let’s say you build a city right on the borders of a neighboring state. He justifiably doesn’t like it and may decide to forgive you if he likes you or is afraid of you, or he pushes politically and says, “Give us the city immediately, or it will be bad!”

You can allow or deny at that moment. And if you refuse, it does not automatically mean war – the other side again has the opportunity to think carefully about how strong an excuse to fight for the matter. It happened to me that opponents rattled their swords, threatened to destroy me if I did not free their fellow believers, but when I did not jump on their bluff, they pulled their tails, rather than risking a conflict with an unpredictable result. Neville Chamberlain would be at home in Humankind.

Even when war breaks out, diplomatic chakras remain interesting. It is rare for a faction to be completely destroyed, the loser will rather become a vassal or give something to his conqueror. It’s nice that in the late parts of the game you don’t get into a situation where only the two strongest empires are alive. And even if the Celts are occupied by the Mongols throughout the game, you can always connect with them and support their national revolt.

Curiosity is appropriate

A lot can change until the release, and it’s true that great strategies of this type need to be devoted to days and weeks, not hours, so that one can competently evaluate them, but even so, after the experience from the demo, I’m pretty sure that we have something to do. to enjoy. Again, Amplitude developers are demonstrating that they understand the strategic genre and can do it a little differently than anyone else.

Yes, I’m definitely not excited about the somewhat untightened mechanism of mixing individual civilizations, but even if the authors didn’t change anything about it, Humankind wouldn’t lose the newly acquired place among my most anticipated games of the year.