Star Trek by George Lucase -apkrig

The history of Star Trek games is brimming with titles that were supposed to be created but not created. Unfortunately. You have already read about several of them on the Vortex – Star Trek: Borg Assimilator, Star Trek: Voyager, Star Trek: First Contact or Star Trek: Secret of Vulcan Fury. As a rule, these were relatively well-known and well-mapped projects, although when analyzing them, I always managed to find a few lesser-known facts that surprised me, for example. The game we will look at today, on the other hand, is almost unknown. And even for rock fans. Despite the fact that her story has at least paper preconditions for anyone to be interested in it on the contrary. But we will delve deeper into the past than in past cases. Already in 1988, Star Lucas could be created by George Lucas.

We have some details coming from several versions of the design, which the Lucasfilm Games studio was to address to Simon & Schuster in 1988.

To put it in perspective right at the beginning. George Lucas himself probably didn’t have much in common with the project, but he was to be born in his game studio Lucasfilm Games, which was founded in 1982 and later became even more famous under the name LucasArts. Among other things, the team gave the world a number of successful adventures on the SCUMM engine, games such as Maniac Mansion, Day of the Tentacle, Sam & Max Hit the Road and the Monkey Island and Indiana Jones series. And the SCUMM engine (Script Creation Utility for Maniac Mansion) was to be used by the intended Star Trek adventure.

The very fact is how little is known about it. Star Trek fans are in the habit of thoroughly mapping the smallest detail, including many unrealized games. However, you would look for more information about this in the usual places in vain. We have to rely exclusively on photographs of period documents that from time to time one of the participants in the surge of nostalgia publishes on Facebook or Twitter. We have some details coming from several versions of the design, which the Lucasfilm Games studio was to address to Simon & Schuster in 1988. At that time, she already had a Star Trek: The Kobayashi Alternative (1985), Star Trek: The Promethean Prophecy (1986), Star Trek: The Rebel Universe (1987) license, and in 1998 she released Star Trek: First Contact. But most of them were text adventures and games with simple graphics.

Star Trek games from Simon & Schuster

Star Trek: The Kobayashi Alternative, Star Trek: The Promethean Prophecy, Star Trek: The Rebel Universe, Star Trek: First Contact, Star Trek: Klingon, Star Trek: Borg, Star Trek: Starship Creator, Star Trek: Deep Space Nine: The Fallen, Star Trek: Starship Creator Warp II, Star Trek: Deep Space Nine: Dominion Wars

Star Trek: The SCUMM Game, as the project was branded, was supposed to be much more ambitious. It would be a film-based graphics adventure powered by the then brand new SCUMM engine, first used by Lucasfilm Games’ Maniac Mansion in 1987. Ron Gilbert, David Fox and Noah Falstein worked on the design, while Gary Winnick took care of the illustrations. . Their names should be at least familiar to LucasArts fans. Since we are still talking almost about the prehistory of Star Trek games, there was no need to invent a revolution. It would be another Enterprise adventure with its original crew. And although, as has already been said, we have several different versions of the proposal, which has gradually evolved, we lack a lot of information. Nevertheless, we can compose at least the basic skeleton of the intended title.

The concept was created and developed at least from April to May 1988. It would be a story game that would combine adventure with action passages. The player would control several different characters, including senior Enterprise officers. During the game, we would switch between them and each would have special abilities and skills corresponding to their specialization and classification. Thus, not every officer could use every device or console, or he would give the player only limited information after such an action. For example, a healthcare professional would have little knowledge of weapon systems while being able to read an accurate diagnosis from a medical tricorder. If the player wants to achieve the best possible result, have the most detailed information and use the thing correctly, he must reach for the right figure and equipment.

For example, as in the series, it would be possible for some of the heroes to land on an alien planet or ship, solve something there, and the rest of the crew struggled with their own problems aboard the Enterprise.

We don’t know anything specific about the story. The authors did not go far on this point. After all, the relevant section begins with the idea that they should find and hire experienced authors to help with the script and dialogues. Rather than outlining a specific plot, it is a set of commitments and rules that the team wants to follow. The story is supposed to have classic Star Trek elements that can be created in the game. For example, as in the series, it would be possible for some of the heroes to land on an alien planet or ship, solve something there, and the rest of the crew had their own problems aboard the Enterprise. According to the authors, it would be possible to bring these situations into play, with the possibility of controlling more characters and solving various problems.

The game should, of course, be as authentic as possible and true to the original. Originally, it seemed that the authors were mainly inspired by the first series and promised not only action and tension, but also the humor and moral dilemmas that belong to Star Trek. For its time, the game was to offer a film spectacle, various alien worlds and action scenes with cuts. In other words, the authors described that they could imitate the style and appearance of a series episode thanks to the graphics. The developers also wanted players not to end up in a dead end and always had some alternative solution to the problem. A funny note is that the team would be able to create the entire Enterprise with all the decks and rooms, but instead will create only the important and interesting places.

As for the already mentioned action, in addition to the adventure, the game would really offer such sequences where it would depend on speed or dexterity. The story could then move forward a little differently or continue differently. The characters could fight directly with or without the phaser, but there would also be spaceship collisions. In this way, players could, for example, squeeze more speed out of the Enterprise if they could handle the ship’s warp core. But as already mentioned, the developers planned to avoid dead ends, so a failure in the action passage would not necessarily lead to the end of the game. Any situation that involves action would offer an alternative way to solve the problem, usually in a logical way. The authors give two hypothetical examples.

The prisoner escapes from the infirmary, seizes the phaser and heads for the transporters to escape back to his ship. You can try to stop it with the help of force, where it can be stunned in a series of action passages. If you don’t succeed, or you just don’t like such sections, you can enter the Jefferies manhole with Scotty, for example, and interrupt the power supply to the transporter. Another example is an emergency call. The Enterprise must respond to calls for help and get quickly to a planet that is being attacked by Klingons. With Scotty’s help, you can squeeze above-standard performance out of the Enterprise drive, but you run the risk of failing and failing. If successful, you will arrive on time and catch the Klingon ship in the system and fight. If you can’t increase your speed, or just don’t try, you’ll be late. But the game does not end, you still have how to continue. You will be transported to the surface of the planet and you will find clues with which you will find out where the attackers went on. Action and logical solutions should be equal and just as fun. That would be very imaginative, of course, but also quite complicated.

In a way, however, his principles and ideas have been preserved. The whole concept, including a mix of logical puzzles and action as well as control of more diverse characters, is strikingly reminiscent of adventures from the company Interplay.

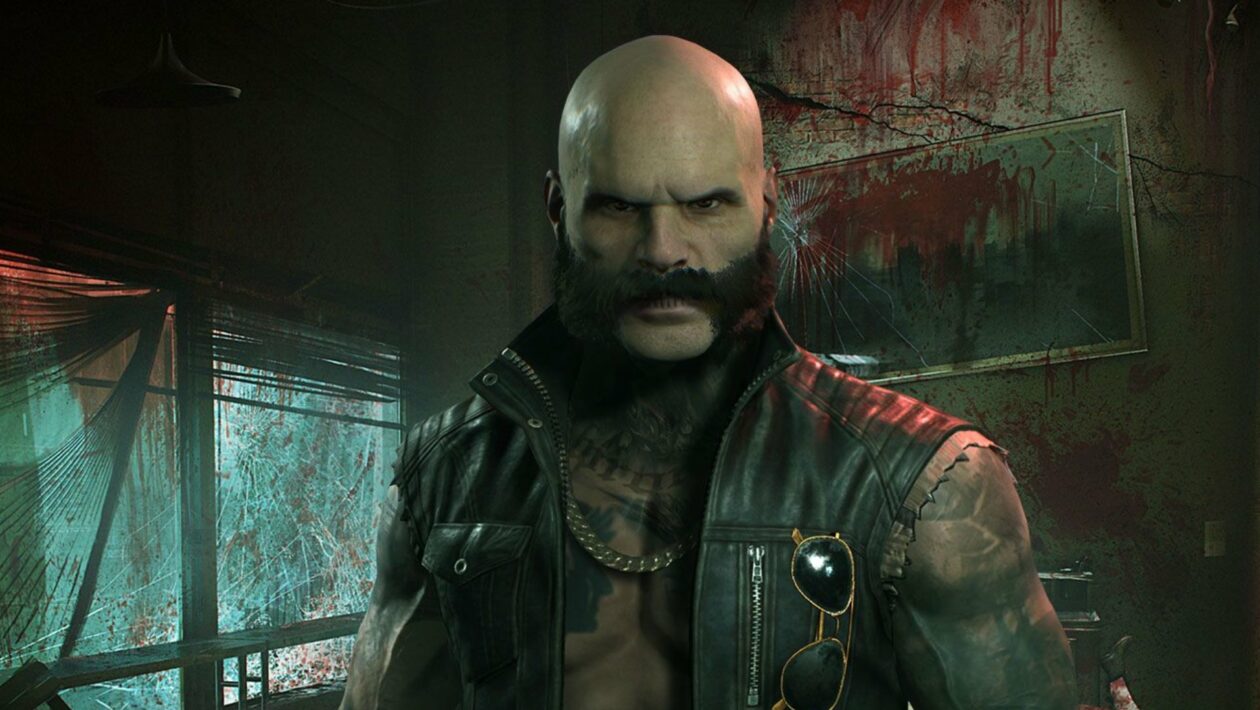

Interestingly, there are smaller and larger deviations in the different versions of the design as the document has evolved. For example, the authors mention that they will expand the capabilities of their engine to suit the situations in Star Trek. As it turned out, at first it seemed that the game would be based mainly on the original series, but in other versions of the documentary there is a mention that the authors want to draw from the films, include the new Enterprise and links to film adventures. The preserved accompanying illustrations created by Gary Winnick would also correspond to this. On them, we can clearly recognize the uniforms used since the second film, interior design and the form of Klingons, which corresponds to the film ones.

The game was to target PCs and similar computers as well as Macs. The team wanted to present the design to Simon & Schuster and illustrate the individual situations at the game Maniac Mansion. But we do not know the most important thing. It is not really clear why the project was canceled or at what moment it did not continue. In a way, however, his principles and ideas have been preserved. The whole concept, including a mix of logical puzzles and action and control of more diverse characters, is strikingly reminiscent of Interplay adventures – Star Trek: 25th Anniversary (1992) and Star Trek: Judgment Rites (1993) – and Star Trek: The Next Generation – A Final adventure Unity from Spectrum HoloByte and MicroProse. It’s also funny because in the early 1990s, George Lucas wanted to merge Lucasfim Games with Interplay. And illustration author Gary Winnick again became the art director of Star Trek: The Next Generation – A Final Unity for a change.